The Lieber Code

Special Edition (April 24, 1863)

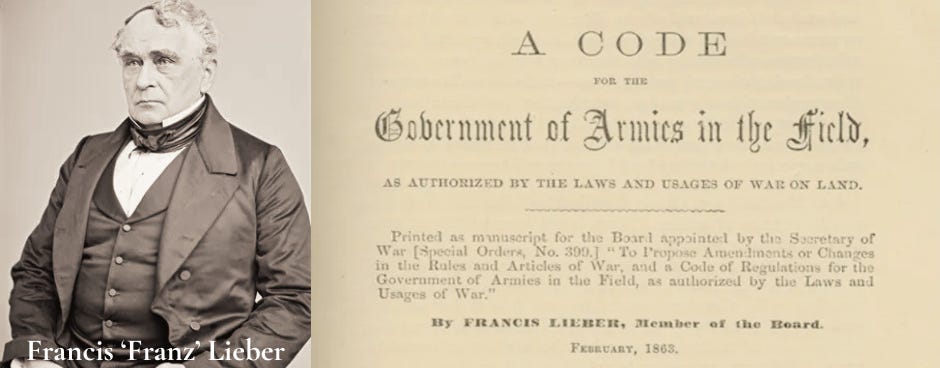

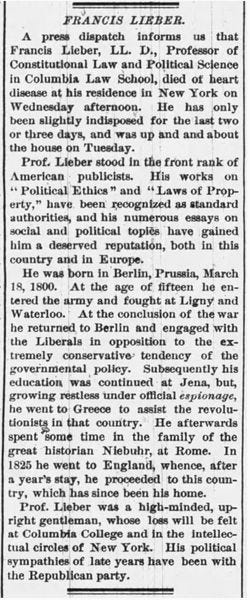

On April 24, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed and the War Department issued General Orders No. 100 detailing the “Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field.” The order was written by Francis Lieber, a German-born professor at Columbia Law School, and provided a set of regulations to govern the conduct of a country's military and naval forces. The first U.S. Articles of War (69) were established by the Second Continental Congress in 1775 (It went into effect upon ratification in 1788.) These were superseded in 1806 when the U.S. Congress enacted an updated Articles of War (101), which had been effect since the start of the war.

The 1806 Articles of War did not address many issues facing Union commanders during the Civil War, such as the management and disposition of prisoners of war, guerilla and partisan fighters, and escaped slaves. General-in-Chief Henry Halleck commissioned Professor Lieber to write a set of guidelines that were specific to “modern” warfare. Once these were established, an editorial committee of Union generals (E.A. Hitchcock, Geo. Cadwalader, G.L. Hartsuff, and J.H. Martindale) went to work revising these guidelines. Once they were completed, Halleck requested that Lieber write a set of comprehensive military laws to govern the prosecution of the war. This would give each Union military commander a set of rules to follow in their engagements with Confederate forces and in occupied civilian territory.

The Lieber Code was the first modern codification of European and international laws of warfare into U.S. military law. In 1864, Lieber’s work became the basis for the first Geneva Convention which focused on the treatment of wounded and sick soldiers. It also became the basis for the Hague Convention of 1907 which established military law for the signatory countries. The Prussian army translated and endorsed the Lieber Code as a guideline for its soldiers in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. The Netherlands published a similar manual in 1871, as did France (1877), Switzerland (1878), Serbia (1879), Spain (1882), Portugal (1890), Italy (1896), and the United Kingdom (1884).

From the Library of Congress:

“The Lieber Code consists of 157 provisions that deal with a wide range of legal issues that must be considered in armed conflict. It contains general principles, but also very detailed rules. Among the issues addressed are whether armed force is justified by military necessity, the principle of humanity, the distinction between combatants and civilians, POW status, retaliation, and permissible methods and means of warfare.”

One of the main tenets of the Lieber Code was that “men who take up arms against one another in public war do not cease on this account to be moral beings, responsible to one another and to God.” In addition, according to the code, “military necessity does not admit of cruelty” or the “infliction of suffering for the sake of suffering or for revenge.” The code also outlaws the use of poison, “wanton” devastation, torture, and assassination. The Lieber Code was never adopted by the Confederate government because it did not distinguish between soldiers based on color or race, and insisted that “so far as the law of nature is concerned, all men are equal.” As such, slaves that escaped were considered to be free, and all captured soldiers must be treated as prisoners of war. Lieber concluded that “the ultimate object of all modern war is a renewed state of peace,” and that “the more vigorously wars are pursued the better it is for humanity.”

The final section of the Lieber Code dealt with the differences between insurrection, civil war, and rebellion. Insurrection was defined as “the rising of people in arms against their government.” Civil War was “war between two or more portions of a country or state, each…claiming to be the legitimate government.” And rebellion was “a war between the legitimate government of a country and portions of provinces of the same who seek to…set up a government of their own. He concluded, “The adoption of the rules of regular war toward rebels…does in no way…imply a partial or complete acknowledgment of their government.” And, the final rule in the Lieber Code was unequivocal: “Armed or unarmed resistance by citizens of the United States against the lawful movements of their troops is levying war against the United States, and is therefore treason.”